A new project of the Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey, Storms of the Past, Stories for the Future, investigates the relationship between memories of past storms and perceptions of storms yet to come. Although the ultimate objective of this project is to provide policy-relevant information for planning purposes, its method is not to forecast the future but rather to document the “futures past” of historic storms. How do memories of past storms inflect the histories of post-storm recovery and rebuilding?

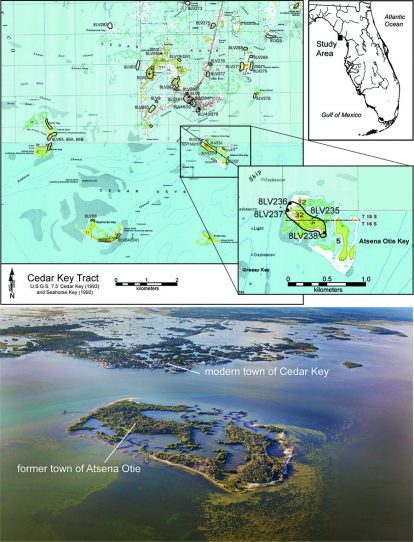

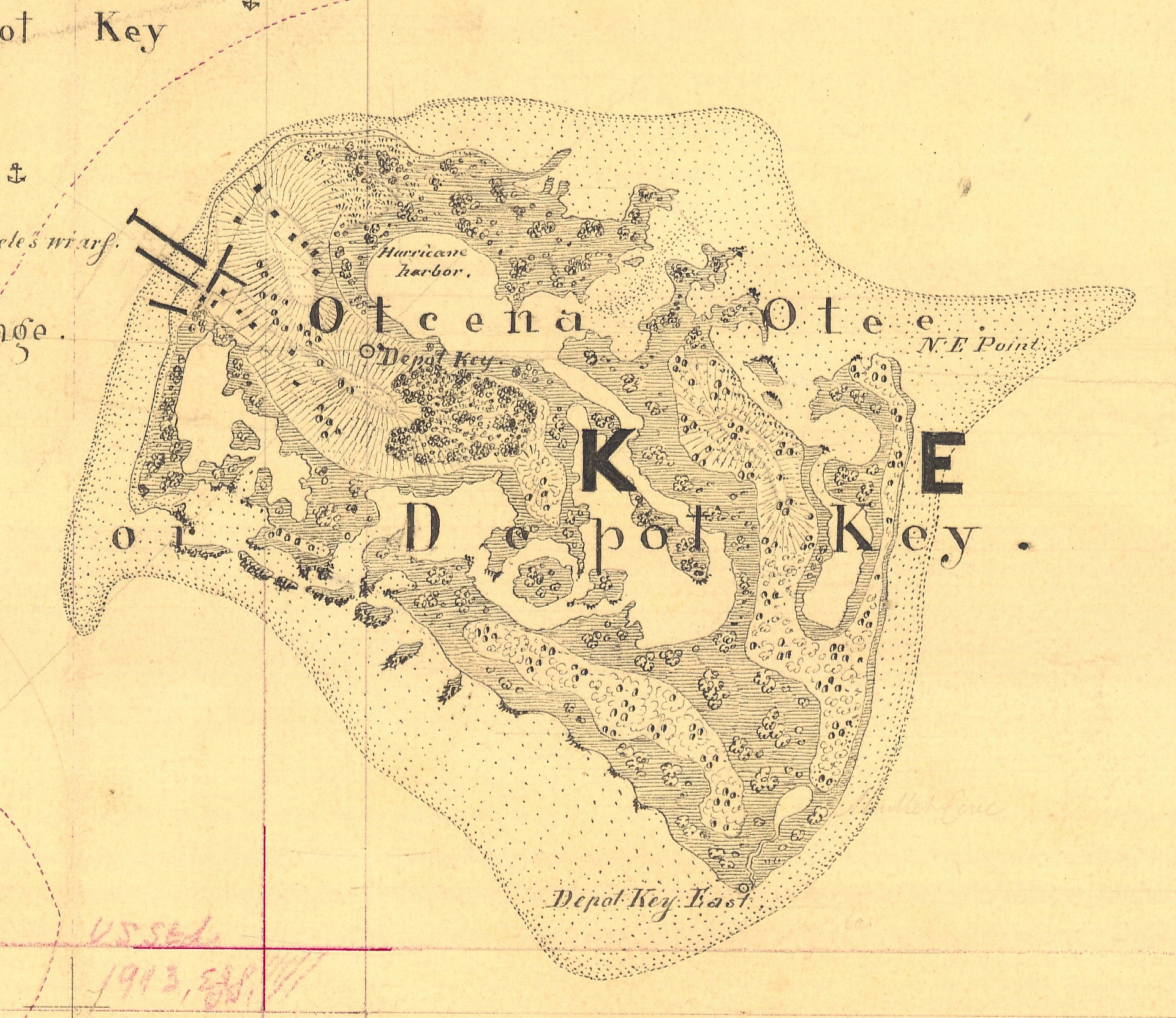

The initial focus of the project is the history of the Gulf-coastal island town of Atsena Otie, locus of a cedar mill industry and associated community that experienced a devastating hurricane in 1896. Among the nation’s leading producers of slats for making pencils, the cedar industry did not recover and eventually the town was abandoned. The island is now part of the Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuge, where visitors find few visible traces of the once-thriving community. With limited material connection to this recent past, memories of Atsena Otie are vague and often misleading. Because the abandonment of Atsena Otie portends one possible future for the modern town of Cedar Key, its history holds more than nostalgic value.

Archaeological work in support of this project is focused on the remnants of the Faber Mill, which are nearly gone thanks to shoreline erosion, as well as a few home sites for which we have good information about ownership and life history. Excavations will serve the dual purpose of providing precise locations for the virtual reconstruction of buildings and related features while also providing tangible connections to the persons who lived and worked in these buildings. We are fortunate that some of the homes that survived the 1896 hurricane were relocated to Cedar Key in the early 20th century. The Parsons home, for instance, now sits at the corner of 1st and E Streets in Cedar Key. A full 3D scan of this structure can be “deconstructed” to remove any modifications since it was moved and then returned virtually to its original location on Atsena Otie.

No matter how compelling a virtual Atsena Otie may be, it will not serve its intended purpose if we fail to understand why the place was so vulnerable to the storm’s impacts and why it was not possible to rebuild in place. We know, for instance, that the cedar industry was already on the wane because of overharvesting and lack of replanting. We also must take into account the changing routes of the railroad that connected the Gulf with the Atlantic Ocean across north Florida, the effects of a global recession in the 1890s, bouts of yellow fever, race relations, and shifting demographics. And finally, if we hope to be able to provide insight on future coastal living in the Cedar Key area, we have to work on the links between experience and expectation in human terms. Taking the long view, it is not unreasonable to suggest that Cedar Key will have to be abandoned and relocated in the future. Will the memory of Atsena Otie have any role in this potential future?

Kenneth E. Sassaman

March 2021