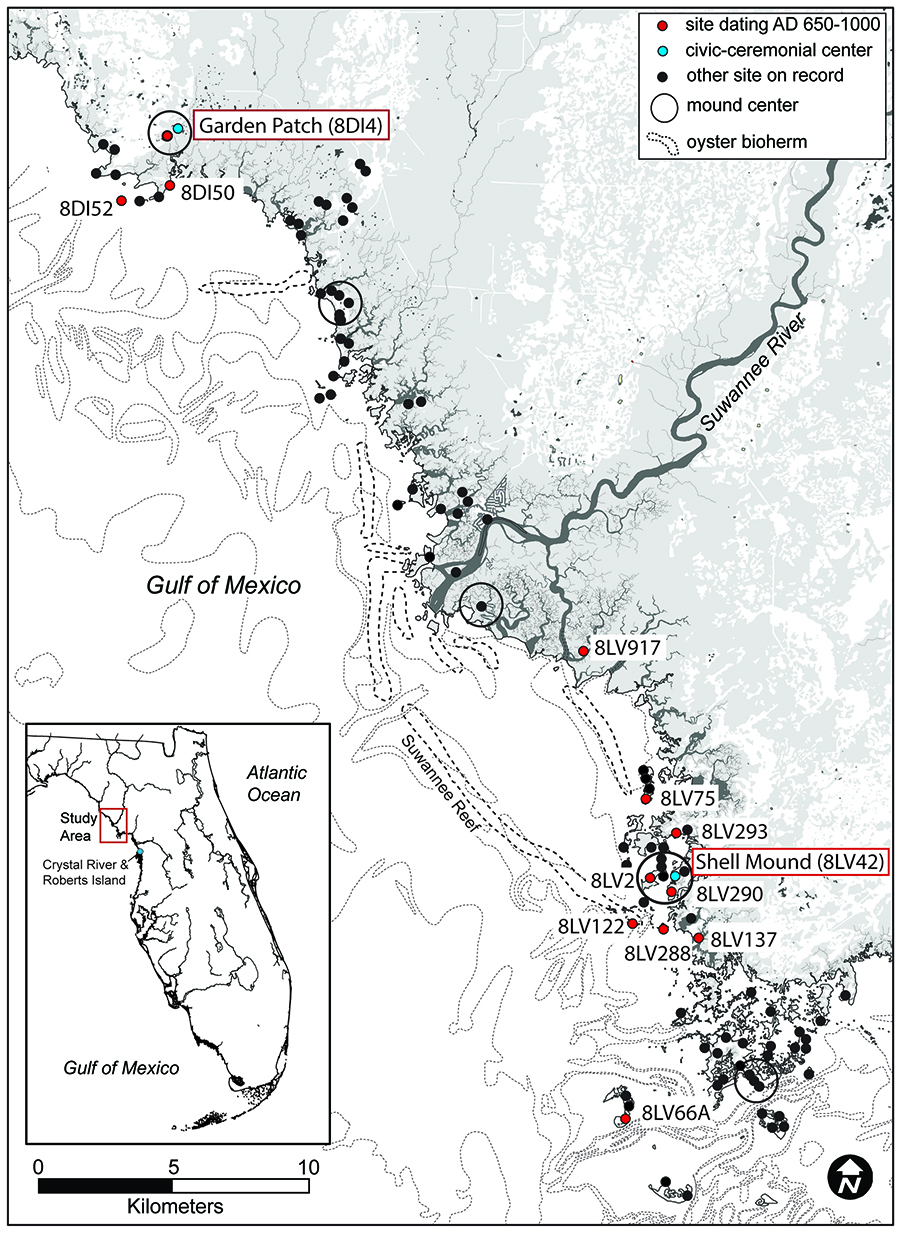

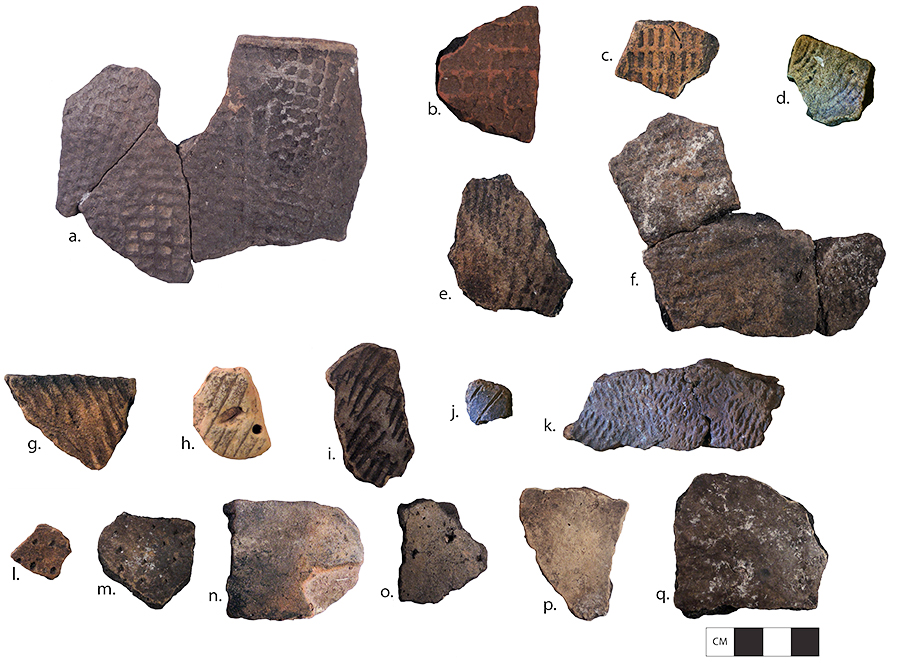

At about 650 CE life changed in the Lower Suwannee region of Florida’s northern Gulf Coast: civic-ceremonial centers that were once places of large gatherings and feasting events were abandoned and people dispersed across the landscape, creating diverse settlements mostly distanced from places of the dead. With this change in settlement came a suite of new, diverse, and elaborate pottery styles, as well as a revival of pottery styles that came before. The changes that took place in settlement and material culture at this time mark the transition from the Middle Woodland period (200-650 CE) to the Late Woodland period. In the absence of evidence of devastating external forces of change (i.e., warfare, natural disasters, epidemics, etc.), I hypothesize that the social transformation that occurred around 650 CE was the result of social movements aimed at changing the status quo.

Living in the year 2020, the transformative effects of social movements are felt every day, particularly in the era of social media and 24-hour news. Through collective action, especially the Black Lives Matter Movement, culture is changing dramatically. Public opinion concerning the Black Lives Matter Movement has shifted substantially since May 25, 2020, and according to the New York Times, as of June 10, 2020, 76 percent of Americans (up 26 points from 2015) now consider racism and discrimination to be a “big problem.” Major cultural players such as the NFL, Netflix, public universities, and even Baskin Robins, have issued public statements (mostly) in support for the cause; more cities, states, and universities have declared Juneteenth an official holiday; and at the same time there has been an array of controversial changes in material culture.

Members of this social movement have taken to the streets throughout the country, toppling statues of Confederate leaders, slave owners, and other figures associated with racial injustice; Confederate flags have been banned from NASCAR; participation in the movement is being publically symbolized through graffiti and hashtags on social media; and the image of the clenched fist, which has historically symbolized resistance and Black liberation, has been adopted as the official symbol of the movement. At the same time, counter-movements targeting the Black Lives Matter Movement (as well as other social movements for reform such as the MeToo movement and LGBTQ rights movement) have adopted and created their own material symbols, including the revival of the swastika and Confederate flag, MAGA hats, and iconic symbols of hate crimes such as the noose.

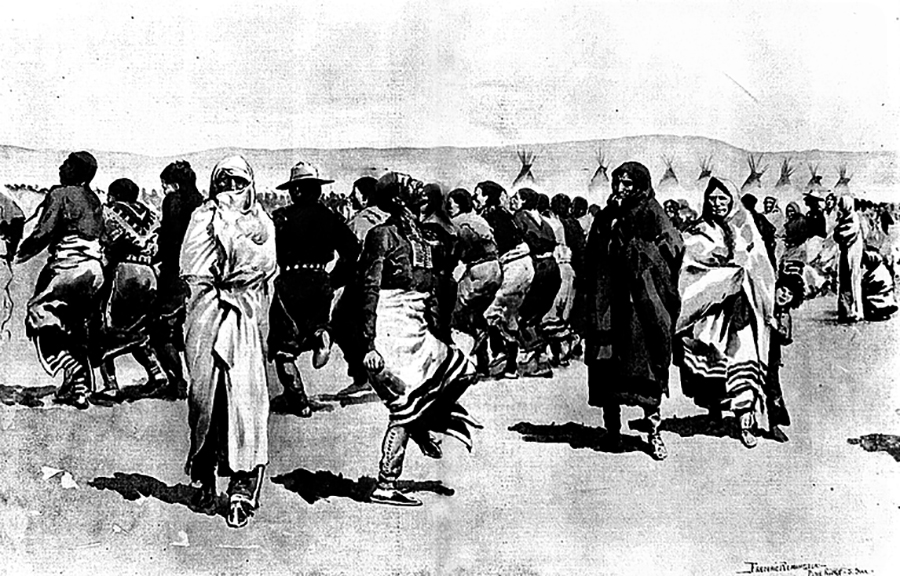

Through the creation, rejection, or revival of particular types of material culture diverse groups of people are unified and collective identity within a social movement (or counter-movement) is publicly expressed. Changes in material culture attending social movements is common throughout history. A well-known example is the Ghost Shirt worn by the Lakota Sioux during the Ghost Dance movement, one of the largest Native American movements during the nineteenth century. Empowered by years of broken treaties, warfare, oppression, disease, and poverty endured at the hands of white settlers, Ghost Shirts arose as a means to protect against the bullets of hostile forces.

Along with shared social identities expressed through material culture, strong social networks are paramount to the success of social movements in enacting transformative change. Put simply, like-minded people who are well connected are positioned for effective and sustained collective action. Through these networks—which today are facilitated by the internet and social media—information and ideas can be shared and collective action can be organized. Examples from history show that stronger social ties create more stability and resilience within movements, and enhances their potential to create lasting change.

Comparing material culture and social connections from the Middle and Late Woodland periods, my dissertation focuses on the role of social movements in the Middle-to-Late Woodland transformation in the Lower Suwannee. While the motivation for change may remain a mystery, I focus on the ways in which populations were able to coordinate transformative action across time and space. Specifically, I plan to use the results of Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) in conjunction with petrographic and technofunctional analyses of pottery to infer changes in social identities and networks attending this transformation. I hope to be able to determine if the seeds of transformation were present in the social configurations of Middle Woodland civic-ceremonialism, and to describe changes in identity and networks as communities dispersed from centers to resettle the area in novel ways.

Based on what is known about the Late Woodland in the Lower Suwannee so far, it seems that there are three types of social movements that are worth considering: (1) a revitalization movement involving the revival of practices related to an ancestral past before the emergence of Middle Woodland civic-ceremonialism; (2) a religious movement involving intensification of mortuary rituals, pilgrimages, and the importation of Weeden Island ceramics and traditions; and (3) a future-oriented movement, which resulted in innovative practices. Any one of these movements had the potential to incite a counter-movement, in which a faction of the population in the region resisted change and continued practices associated with Middle Woodland civic-ceremonialism, albeit at new locations.

While the study of social movements in deep history certainly diverges from my years of research focusing on oyster harvesting practices, the social climate of 2020 is inspirational to my work. By tracing social movements in history, insight is gleaned regarding the importance of a range of variables including community security, collective identities, social networks, mechanisms of collective action, and the built environment in navigating a transforming physical and social landscape. In its emphasis on materiality and material conditions of human experience, I believe that archaeology holds good potential for contributing to the cross-cultural study of social movements well beyond the reach of ethnography, sociology, and literary history. The analysis of early social movements is particularly relevant today in considering the variables related to the success of such endeavors, as well as the potential transformative effects that social movements can have across community, political, and environmental dimensions.

Jessica A. Jenkins

June 2020