Now in its third decade of intermittent activity, the Soapstone Vessel Dating Project started out of necessity. Working in the 1990s at upland Sandhills sites in South Carolina, my colleagues and I rarely encountered datable organic matter. The occasional sooted pot sherd offered some hope for direct dating via AMS, but we were resigned to the fact that our age estimates would depend on stratigraphy and cross-dating diagnostic artifacts from sites with better organic preservation. At a site on a tributary of the Savannah River, Tinker Creek (38AL224), we encountered out first sooted soapstone vessel sherd among pottery sherds of the Stallings and Thoms Creek traditions, some of the oldest pottery in the region. Cross-dating the soapstone sherd with sites elsewhere, we estimated it would date to at least 4,500 radiocarbon years ago, when the first pottery was then-dated to have appeared. The precedence of stone bowls over pottery was gospel in archaeology at the time. All textbooks and syntheses on archaeology in the Eastern Woodlands viewed stone bowls as the precursor to pottery, a veritable “Stone-Age” prototype of the “Neolithic” innovation of hardening clay with fire to make durable containers. At 3160 ± 60 B.P., the AMS age estimate on soot from the soapstone vessel sherd we uncovered from Tinker Creek was a bit of a surprise.

In reviewing the regional literature on soapstone vessels, I was drawn to the work of Dan Elliott. In a variety of projects starting in the 1980s, Dan encountered stratigraphic evidence that suggested soapstone vessels in the Savannah River Valley of Georgia and South Carolina actually post-dated the inception of pottery, a radical idea for the times. Pottery is indeed especially ancient in this region and for many centuries even before pottery appeared, local communities quarried soapstone to make slabs for indirect-heat cooking. But they evidently did not craft bowls from soapstone until pottery was widely available; in at least this part of the Southeast, pottery took precedence over stone bowls.

As opportunities and funds allowed, I started to collect AMS dates on sooted soapstone sherds from across the Southeast. At the same time, I reviewed carefully the contexts in which soapstone was alleged to predate pottery, which was mostly from sites in North Carolina. I found that evidence for an earlier age for soapstone vessels was pretty thin and that analysts may have downplayed contrary observations because the sequence of stone-to-pottery was so deeply ingrained in the culture history of the Eastern Woodlands. As AMS dates accumulated I decided that Dan Elliott was not only right about the counter-intuitive sequence, but that this was a widespread phenomenon, not simply a local anomaly due to especially old pottery in the Savannah River Valley. The early results of the Soapstone Vessel Dating Project were published in 1997 in Early Georgia.

The project gradually expanded into the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast regions, where soapstone vessels abound and likely predate pottery in many cases but also enjoy a resurgence much later, during the Early Woodland period. A 1999 chapter in an edited volume on the Northeast compares the region’s chronology to that of the Southeast to assess patterns of innovation and diffusion. What began to emerge from these comparisons and the ongoing dating project was that soapstone vessels could not be understood simply as utilitarian items. They were transported over long distances, they were something cached, and, in late-period contexts, sometimes interred with human burials. I was particularly struck by the fact that the greatest concentration of soapstone vessels anywhere in the Eastern Woodlands was at Poverty Point in Louisiana, hundreds of kilometers from the nearest sources of soapstone. Because Poverty Point residents had knowledge of pottery and occasionally used it, the importation of literally tons of soapstone was not likely a matter of practical concern.

Working independently on dating and sourcing soapstone in the Northeast, James Truncer published an article in American Antiquity in 2004 that took exception with my debunking of early contexts for soapstone bowls. Accepting early age estimates I had discounted, Jim argued that soapstone vessel technology was around for as much as 2,000 years before it peaked in use ca. 3,500 radiocarbon years ago. I rebutted his argument in American Antiquity in 2006 with the suite of about two dozen AMS soot dates available at the time, and have since reiterated the argument in several other papers: with some notable exceptions, pottery predated or was coeval with soapstone vessels in most of the Southeast. I suspect but cannot prove that this also holds true for the Mid-Atlantic and much of the Northeast, but I am certain it does for the Southeast. Explaining this pattern requires looking beyond any culinary uses of soapstone to consider its role in exchange, ritual, and even cosmology. Places like Poverty Point, Claiborne in Mississippi, and Bird Island and Queen’s Harbor (Greenfield) in Florida offer clues in the various caches they contained, usually in association with human burials. Early Woodland uses of soapstone vessels in the middle Tennessee River Valley include other good examples of nonutilitarian value. None of this means that soapstone vessels were not used as containers for processing or preparing food or other substances—for indeed they would not be sooted so often were they not put to use over fire—only that a cost-benefit analysis that considers just utilitarian concerns will fall short of accounting for the timing and distribution of these incredible items.

As of July 2020, the project database includes a total of 45 AMS assays on soot from soapstone vessels from 24 sites in the Southeast, details of which can be downloaded here. The database includes AMS assays on only soot or related organic residues from vessel sherds themselves. It includes assays obtained by the project directly, as well as those obtained by others, mostly in the context of CRM projects (see spreadsheet for sources).

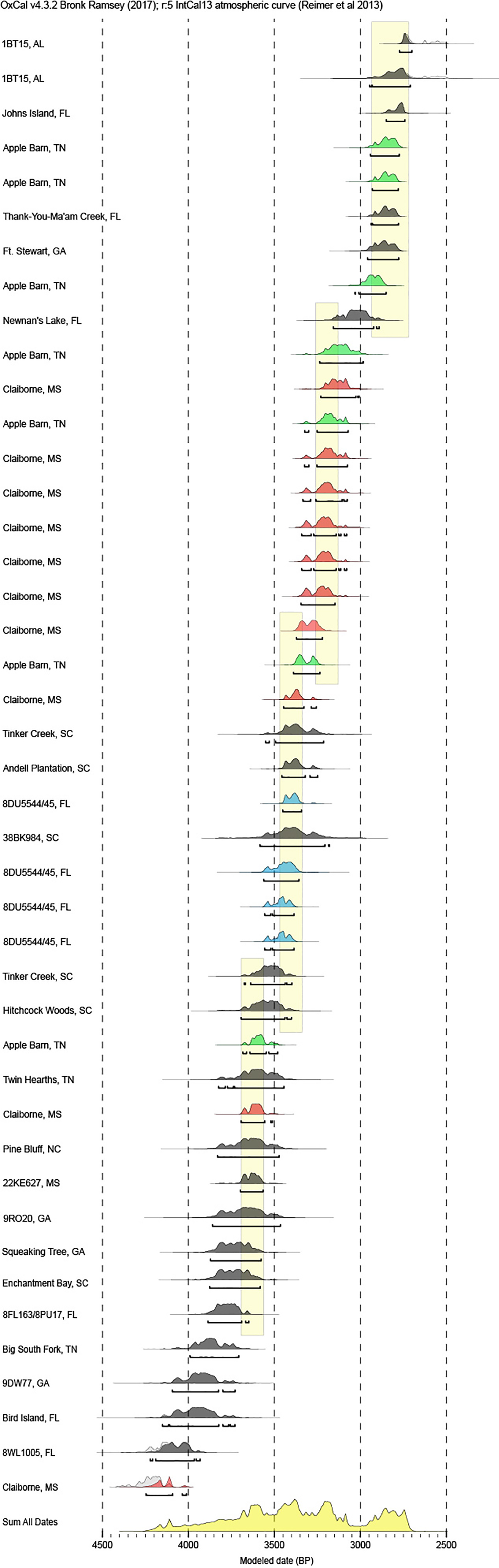

An OxCal-derived graph of individual and summed probabilities for 43 of these assays follows below. Omitted from this display are two far outliers: the 6240 ± 40 B.P. date from a sherd excavated at Mitchell River in Florida, and the 6180 ± 40 B.P. date from one of 12 soapstone vessels in a cache at Claiborne in Mississippi, which Sam Brookes and I reported recently. The latter context clearly brings these outliers into question: because the cache is so well dated at ca. 3000-3100 radiocarbon years ago, the inclusion of a 6,000-year-old vessel means one of three things: (1) a soapstone vessel was curated for 3,000 years; (2) it was discovered and reanimated 3,000 years ago in the manner of archaeological excavation or survey, or (3) the assay reflects contamination from old carbon. Although the old-wood problem may be at play here, both Claiborne and Mitchell River are located on the Gulf Coast, where asphaltum from underwater oil seeps occasionally washes up on shore. A great mastic, asphaltum may have been used to coat or repair soapstone vessels, introducing old carbon to surfaces that accumulated more recent carbon from use over fire. Chemical analyses of sherd residues may help to sort this out. In the meantime, these two assays are so far out of stride with other assays on soot—not to mention the large inventory of seventh-millennium sites across the region with no soapstone—to justify setting them aside for now.

The 43 assays in the graph above were calibrated in a one-phase model that assumes continuity between beginning and end dates. The 95-percent probability date range for each assay can be found on the downloadable spreadsheet. Modal tendencies in the summed probability distribution at the bottom of the figure (in yellow) can be attributed in part to sampling, but not entirely. Four modes stand out, highlighted in the graph by vertical yellow bars that span the assays involved. The first mode, at ca. 3700-3550 cal B.P. consists of assays from 11 different sites across much of the Southeast. These are not the oldest assays but it is noteworthy that they all postdate the end of the Classic Stallings phase of the middle Savannah River Valley, known for early pottery and the use of soapstone slabs for indirect cooking, but not soapstone vessels.

The second mode at ca. 3450-3350 cal B.P. consists of 12 assays but from only eight sites. Four are from the Queen’s Harbor (Greenfield) site (8DU5544/55) near Jacksonville, Florida (in blue), locus of a mortuary cache of large but fragmented vessels. Samples in this mode are otherwise biased towards South Carolina sites, which may be a matter of geographic proximity when the project started there in the 1990s.

The third mode of ca. 3250-3150 cal B.P. consists largely of assays from the Claiborne vessel cache (in red), but also three from the Apple Barn site in Tennessee (in green), reported by Ted Wells in his 2006 M.A. thesis and a co-authored paper in Southeastern Archaeology in 2014. Found largely in Early Woodland context, the Apple Barn vessels account for three of nine assays that make up a late mode of ca. 2900-2700 cal B.P. Although represented here by only one (1BT15), sites with soapstone and sandstone vessels in the middle Tennessee River Valley are arguably associated with Alexander pottery of the Early Woodland period, not the preceramic Late Archaic, as once assumed. Together with the relatively late age estimate for the Claiborne cache, the members of this last mode remind us that the chronology for soapstone vessels has been turned on its head.

The project goes on, even if intermittently. Colleagues with sooted soapstone vessel sherds anywhere in the Eastern Woodlands are invited to get in touch with us for possible dating. Plans are in the offing for a trip to Poverty Point to examine the sherds of a cache reported by Clarence Webb back in the 1940s. Consisting of sherds from scores of vessels, the Poverty Point cache has never been dated. I would imagine that some of them have soot, and if so, I expect the age estimates to be rather late, perhaps coinciding with abandonment of Poverty Point ca. 3100 cal B.P., as was the case at Claiborne. Rather than seeing soapstone vessels as the beginning of a history of durable container use, their timing well past the inception of pottery across the region raises new questions about the value and meaning of these items, particularly in the so-called “transition” between the Archaic and Woodland periods.

Kenneth E. Sassaman

July 2020