A spectacular archaeological site with a generic name lies on the end of a peninsula about 12 km north of the town of Cedar Key. Shell Mound (8LV42) is well known to many people who live in and visit the Cedar Key area, but until recently details of its age and use were few. Since 2012 the LSA has delved into the many mysteries of Shell Mound and now have a reasonably good sense of what happened there between about 400 and 650 CE. Field schools in 2014 and 2015 supplied most of the evidence. Here’s what we know as of 2020.

As the name implies, Shell Mound is a shell mound, although it actually is more of a shell ring. In relief reaching up to 7 m above the ground surface, Shell Mound is a subcircular ridge about 180 x 170 m in outside diameter enclosing an open area about 60 m wide. It doesn’t take an archaeologist to know the size and shape of Shell Mound, but with healthy tree cover, it does not fully reveal itself at ground level. We have benefited from publicly available LiDAR data for making topographic maps of the site, and in 2015 we started mapping it with a total station. All of that was superseded by drone-mounted LiDAR data provided by our UF colleagues at GatorEye. The details of 3D models made from these data are incredible. From this vantage point we can imagine that Shell Mound formed as separate deposits that later blended together into a subcircle, although recent land alterations (dirt roads, some shell mining) account for some of its irregular relief.

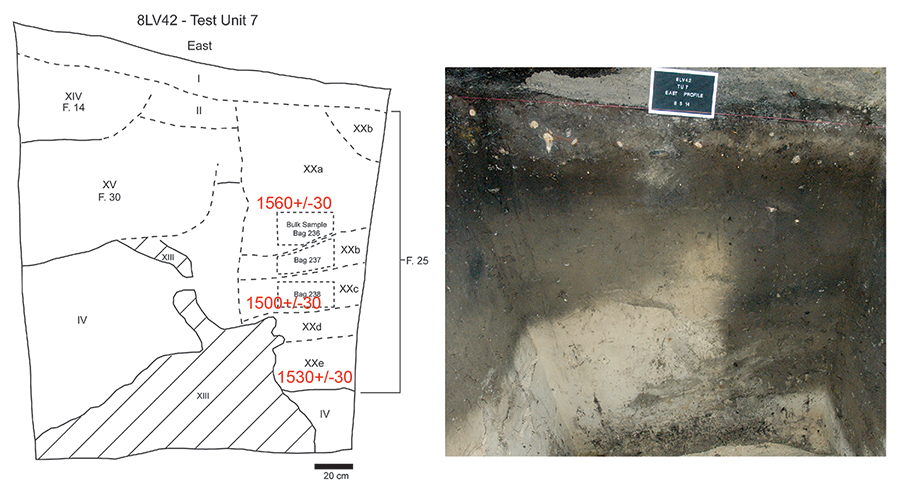

A program of extensive test excavation revealed a more complex picture than Shell Mound’s surface allows. Deposits along the north and south ridges (arcs) of this subcircle are entirely different. The north ridge consists mostly of dune sands, with midden on top and large in-filled pits along the south slope. Much of the south ridge consists of redeposited midden and pit fill from the inside of the north ridge, terraforming that occurred after about 150 years of occupation, ca. 550 CE. Whether done all at once or in phases of individual mounds, construction of the south ridge enclosed what is arguably a central plaza. Our limited testing in this open space provided suggestive evidence for buildings along the interior edge. A small circular village of 10-15 households is a reasonable estimate in need of testing.

We actually know more about events that brought visitors to Shell Mound than we do its resident population. Large pits we encountered along the southern slope of the dune contained abundant vertebrate faunal remains, mostly fish, but also turtles, deer, and the bones of birds, notably those of juvenile white ibises. In M.A. thesis research, Josh Goodwin took a close look at the bird bone from Feature 25, one of several large pits we excavated. With the help of Florida Museum ornithologist Dave Steadman and a longitudinal study of white ibis reproduction on the nearby rookery of Seahorse Key, Josh was able to infer that young ibises were captured in mid- to late June. LSA affiliate Meggan Blessing added the results of analysis of bone from five other pits to substantiate what Josh found in Feature 25. Taken together, the vertebrate fauna from Shell Mound pits point to large-scale events of food gathering and consumption that likely took place around the time of summer solstices, June 21.

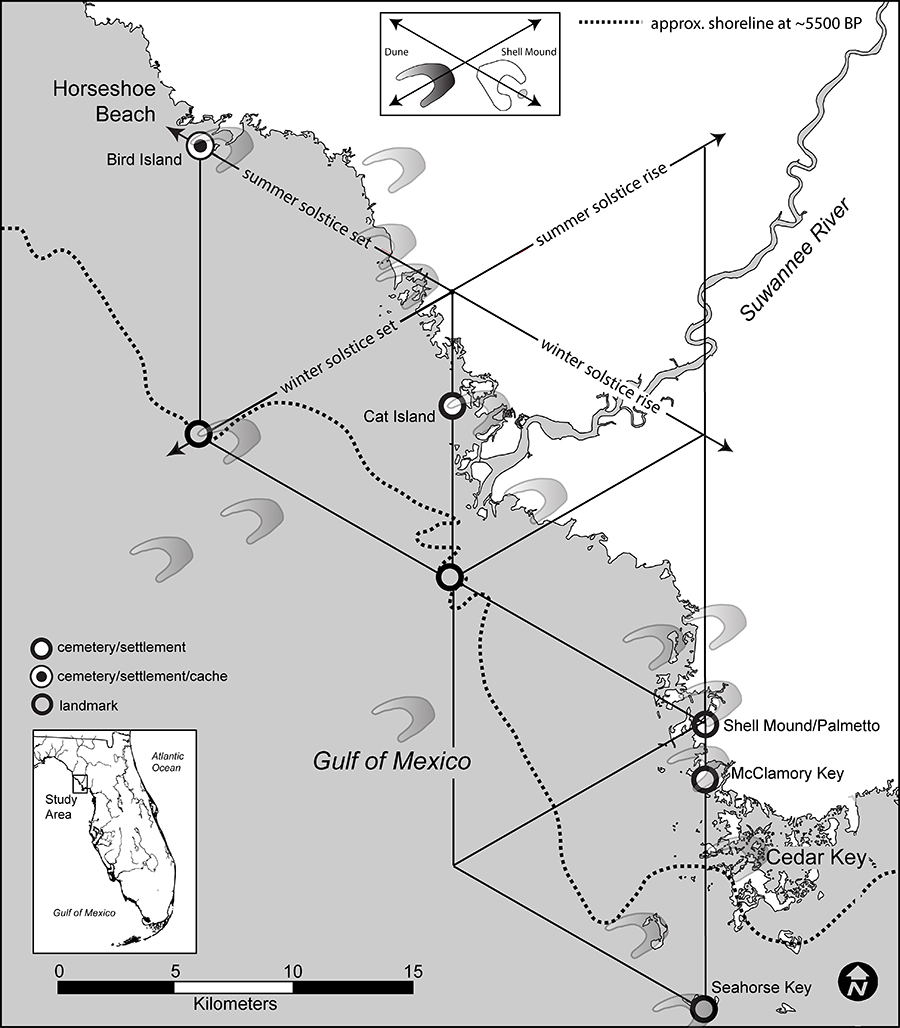

Although estimates of season of capture are never that precise, a summer solstice date is supported by the fact that Shell Mound is located on a parabolic dune that is oriented to the solstices. This is actually a common feature of Ice Age dunes in the study area and it resulted from prevailing winds blowing from the southwest to the northeast at about 60 degrees east of north, the azimuth of the summer solstice rise. This of course is happenstance, but the orientation of dunes up to 2 km long were no doubt noticed by people so attuned to the cyclical movements of celestial bodies. Like the periglacial fissures of bedrock beneath Stonehenge or the erosional rift that is Chaco Canyon, natural features of the landscape with celestial orientations were often valorized by indigenous people as places where the sky and earth intersected. Such places are sometimes considered portals to other realms of existence or places where ancestral beings or forces reside. In this respect, it is hardly coincidental that denizens of the Lower Suwannee region emplaced their deceased on the distal ends of parabolic dune arms stretching towards the opposite of the summer solstice rise, which is the direction of the winter solstice set, 240 degrees east of north. We suspect that at the time it was established no later than 2,700 years ago, Palmetto Mound, located across 500 m of intertidal water to the west of Shell Mound, was at the end of a dune arm. It follows that Shell Mound was probably sited in relation to Palmetto Mound although its connection to summer solstice feasts is uncertain.

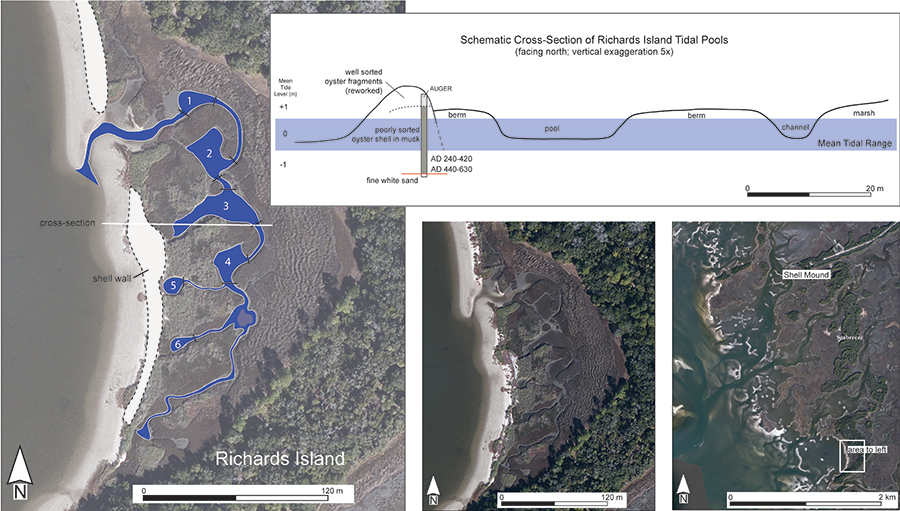

Juvenile white ibis bones are our best indicator of mid- to late-June feasting, but the most prevalent bony remains in pits come from mullet, a fish that historically was taken in large quantities in the Fall, when they spawn. However, most of the mullet from pits at Shell Mound are from fish about 29 cm in total length, which means they were about three years of age. In the summer of their third year mullet fatten up for their first spawning run out to deeper water of the Gulf. They were evidently captured in mass for Shell Mound feasts, but how? Thanks to a lead provided by seasonal Cedar Key resident Mr. Ed Allen, we think they were harvested from a tidal fish trap at Richards Island , 2 km south of Shell Mound. We have enough evidence to infer that the oyster seawalls of this trap were constructed at the time of Shell Mound feasts. A coeval midden on the north end of the trap is a likely place where mullet and other fish were processed for transport to Shell Mound.

Besides bones and shell, pits also contained the sherds of large cooking vessels and small serving vessels. The cooking pots are tempered with limestone in the local Pasco tradition but the serving vessels include spicule- and sand-tempered forms, some with elaborate shapes and painted red. Although these too could have been local wares, they stand in sharp contrast to the more common Pasco pottery and were likely brought to the site by visitors from elsewhere. The inclusion of nonlocal items such as quartz crystal and mica in pits supports this idea, as does the large size of the cooking vessels, which imply a volume of food production beyond the daily fare of permanent residents.

To understand why people gathered at Shell Mound for summer solstice feasts is to understand the cosmology of Native American ancestors and the place of the deceased in their worldviews. We know from ethnohistoric sources that the cosmos was divided into Upper and Lower Worlds and that the sun traveled between these worlds in daily and annual cycles, the latter marked by solstices on the longest and shortest days of the year. Winter solstice events were most likely connected to the deceased, but we suspect that summer solstice events were akin to the World Renewal ceremonies of the ethnohistoric era. World Renewal was everyone’s business, a matter of maintaining or returning balance between the Upper and Lower Worlds from the mediating place of This World.

There is much more to the story of Shell Mound besides summer solstice feasts, so research continues on the large collection of artifacts, shell, and animal bones to see what else this incredible site has to say. We know enough at this point to explain why Shell Mound was a place of ritual infrastructure and annual gatherings. Through the great resource of Friends of the Lower Suwannee and Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuges and in partnership with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the LSA helped to produce 11 new interpretive panels installed on a walking trail of Shell Mound in November 2018. The next time you are in the Cedar Key area stop by Shell Mound for the 30-minute walk and see why this place continues to be so special.

In the meantime, technical reports of Shell Mound investigations can be found in the list of Publications of this website. Also available are articles from the journals American Antiquity and Cambridge Journal of Archaeology, and the public-oriented archaeology magazine of the Florida Historical Society Archaeological Institute.

Kenneth E. Sassaman

June 2020