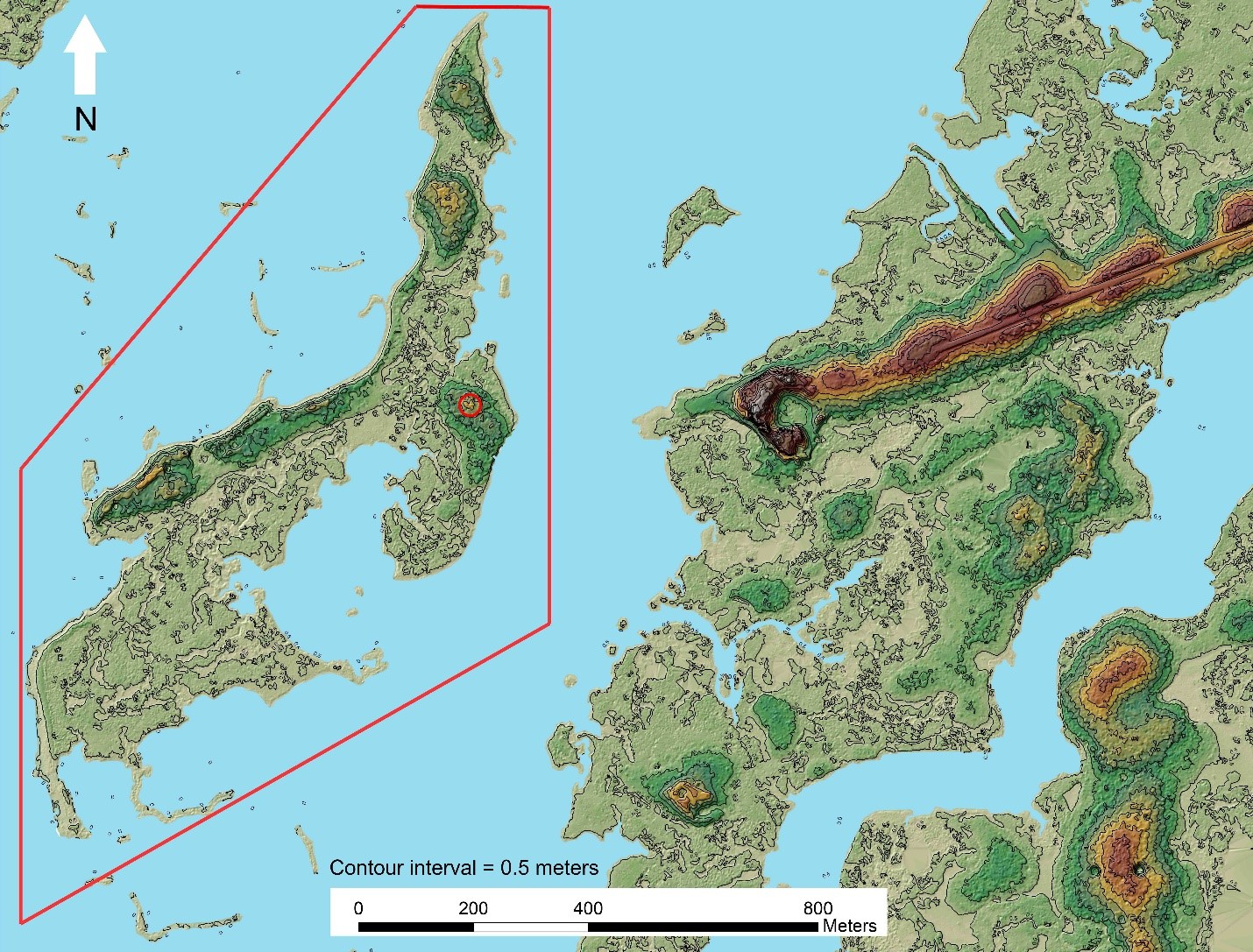

Palmetto Mound (8LV2) on Hog Island is an inconspicuous mortuary mound that nevertheless played an important role in the ritual life of widespread peoples for perhaps two millennia. Hog Island is located along the Florida Gulf Coast, 500 m from the mainland over intertidal water, in the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge. The island is composed of a group of inter-connected hammocks, each of which contains the remains of archaeological sites. Palmetto Mound lies on the eastern-most hammock of Hog Island, directly west of Shell Mound (8LV42) across the water. Palmetto Mound has been called by various names and has been designated 8LV2, 8LV5, 8LV7, and 8LV40. The mound has been left nearly destroyed by professional and avocational archaeologists and looters who scattered its contents among numerous collections, leaving few records of their findings (Donop 2015, 2017).

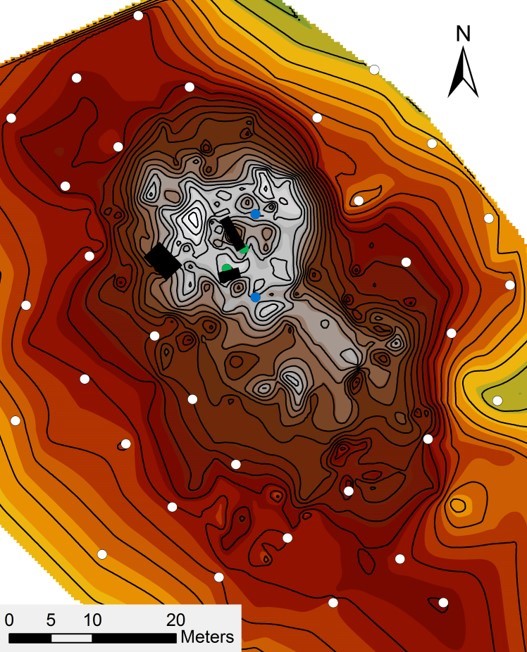

Members of the LSA conducted archaeological investigations on Hog Island and Palmetto Mound from 2013–2015. Investigations included topographic mapping, probing, auguring, shovel test pit surveying, and the excavation of three test units within existing looter pits. Careful attention was paid to minimizing the disturbance of intact burials and none of the human remains encountered in the field were sampled or analyzed; all such remains were reinterred in the pits or units from which they came. The results of the fieldwork indicated that the majority of Hog Island was inhabited for thousands of years, with the exception of the eastern hammock that contains Palmetto Mound, which had been dedicated to the dead for perhaps two millennia.

We suspect that Native Americans were initially attracted to the location by natural phenomena with cosmological significance. Palmetto Mound rests at the distal end of a relict parabolic paleodune naturally aligned to the solstices and surrounded by water, a substance commonly associated with the Underworld by Native Americans, forming a cosmic intersection that made the location ideal for mortuary activity (Hudson 1976). Human remains were interred at the distal end of the paleodune by at least 400 BCE although an AMS assay from carbon residue from a St. Johns Plain sherd from the site indicates that Palmetto Mound may have been founded as early as 890 cal BCE (Sassaman et al. 2017). The practice of burying the dead on the ends of paleodunes dates back to the Late Archaic in the area (Randall and Sassaman 2017).

Palmetto Mound experienced varied periods of growth and ritual activity over its 2,000-year lifespan. The excavations revealed that mortuary activity at the mound included the emplacement of alternating sand and shell midden deposits in the northwestern portion of the mound, from approximately 400 BCE–400 CE. The hammock lacks evidence for domestic habitation and it appears that Native Americans transported the shell midden, composed primarily of eastern oyster, from elsewhere and placed it in discrete deposits that protected and preserved their primary and, increasingly more prevalent, secondary burials in the sand. Ritual activity at Palmetto Mound seems to have temporarily waned between 400–650 CE when major terraforming was carried out at Shell Mound and a second burial mound, the Dennis Creek Mound (8LV41), was constructed ~250 meters to the northeast (Boucher 2017). These sites and others formed a major civic-ceremonial center that was part of a panregional network that collapsed in approximately AD 650 for unknown reasons, after which Palmetto Mound experienced a period of ritual hyperactivity. Collections-based research at several institutions indicates that the mound had once contained hundreds of human burials, nonlocal objects, and elaborate ceramics, including an unusually high number of Weeden Island biomorphic effigies, particularly anthropomorphic ones (Donop 2017). Evidence suggests that many of these objects were purposefully fragmented and deposited in the now-decimated, sandy southeastern portion of the mound during the Late Woodland period, and may have been ritually exchanged in an effort to connect communities dispersed by the collapse (Donop 2019). An AMS assay as late as 1290 CE obtained from carbon residue from a St. Johns Check Stamped sherd from the site indicates that activity at the mound continued well into the Mississippian period (Sassaman et al. 2017).

Today, Palmetto Mound is protected and cannot be visited without permission from U.S. Fish and Wildlife, although signage at Shell Mound provides information about the site.

References

- Boucher, Anthony. 2017. Paths of the Past: An Off-Mound Survey of Shell Mound’s (8LV42) Northeastern Peninsula. Master’s thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville.

- Donop, Mark C. 2015. Palmetto Mound (8LV2). Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey 2013-2014: Shell Mound and Cedar Key Tracts. Technical Report 21, pp. 103–115. Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville.

- Donop, Mark C. 2017. Bundled Ancestor: The Palmetto Mound (8LV2) on the Florida Gulf Coast. PhD dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Florida, Gainesville.

- Donop, Mark C. 2019. Fragmented and Forgotten: Pots, People, and Palmetto Mound (8LV2). Paper presented at the 71st Annual Florida Anthropological Society (FAS) Meeting, Crystal River.

- Hudson, Charles. 1976. The Southeastern Indians. The University of Tennessee Press, Knoxville.

- Randall, Asa R., and Kenneth E. Sassaman. 2017. Terraforming the Middle Ground in Ancient Florida. Hunter Gatherer Research 3:9–29.

- Sassaman, Kenneth E., Neill J. Wallis, Paulette S. McFadden, Ginessa J. Mahar, Jessica A. Jenkins, Mark C. Donop, Micah P. Monés, Andrea Palmiotto, Anthony Boucher, Joshua M. Goodwin, and Cristina I. Oliveira. 2017. Keeping Pace With Rising Sea: The First 6 Years of the Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey, Gulf Coastal Florida. The Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 12(2):173–199.

- Sassaman, Kenneth E., Meggan E. Blessing, Joshua M. Goodwin, Jessica A. Jenkins, Ginessa J. Mahar, Anthony Boucher, Terry E. Barbour, and Mark C. Donop. 2020. Maritime Ritual Economy of Cosmic Synchronicity: Summer Solstice Events at a Civic-Ceremonial Center on the Northern Gulf Coast of Florida. American Antiquity 85:22-50.

Mark C. Donop

June 2020