In 2009 the Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology (LSA) launched a long-term field program in the Lower Suwannee and Cedar Keys National Wildlife Refuges of Florida. Structured by a three-prong approach involving (1) reconnaissance, (2) rescue, and (3) research, the program supports the conservation needs of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages the refuges. Reconnaissance fulfills agency needs for cultural resource inventory and assessment; rescue targets cultural resources facing imminent destruction; and research provides the interpretive context for assessing the significance of cultural resources. The unifying goal of all aspects of the program is development of detailed perspectives on culture and environment in the context of climate change and sea-level rise.

The coterminus Lower Suwannee and Cedar Key National Wildlife Refuges encompass 54,000 acres of federal land along a 42-km-long stretch of the northern Gulf Coast. Like much of the coastline of Florida, this portion of the Gulf Coast is peppered with shell-bearing sites and other locations of ancient human activity. Unlike much of the Florida coastline, however, the Lower Suwannee is one of few river-delta estuarine systems in the U.S. to escape modern development.

Coastal locations in general have long attracted human settlement, and those of the lower Southeast were especially attractive for their rich estuarine and intertidal resources conducive to sustained human exploitation. But coastal dwelling in the lower Southeast has always been a challenge for humans because sea levels have routinely fluctuated with changes in global climate. The Florida Gulf Coast and its offshore shelf slope seaward at a very low angle, which make them especially vulnerable to changing sea level. Since humans arrived in ancient Florida ca. 14,000 years ago, sea has risen about 80 m and the shoreline retreated about 200 km. Sea rose rapidly at the end of the Ice Age and then slowed enough by about 5,000 years ago to enable estuaries to thrive in their more-or-less modern configuration.

In general, coastal sites predating 5,000 years ago that survived the erosion of rising sea are now under water. Modern shoreline sites younger than this are common in the study area, although many are actively eroding and will not survive much longer; some have succumbed to inundation in recent years.

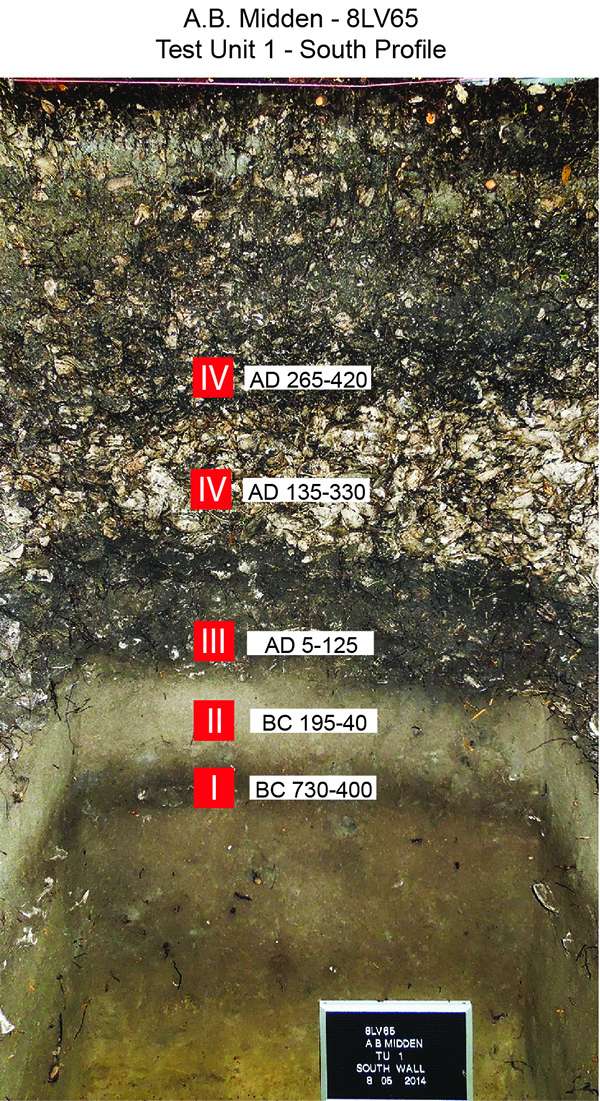

Rescue of sites exposed along shorelines usually entails the excavation of 1 x 2-m test units immediately landward of eroding cutbanks. Middens dominated by the shells of oyster, clam, and other shellfish are often well-stratified and always excellent contexts for preserving the bones of fish, turtles, and other animals. Sites on offshore islands are especially well stratified.

Most of the sites known to us were first located by local citizens who noticed shell and artifacts at locations of active erosion. Shoreline exposures of shell middens sites are conspicuous and can be located from watercraft capable of navigating the shallow water of low tide. Landward of shorelines surface visibility is hampered by dense vegetation and leaf litter. Reconnaissance of the interior portions of islands and other near-shore landforms thus requires shovel testing to locate subsurface deposits.

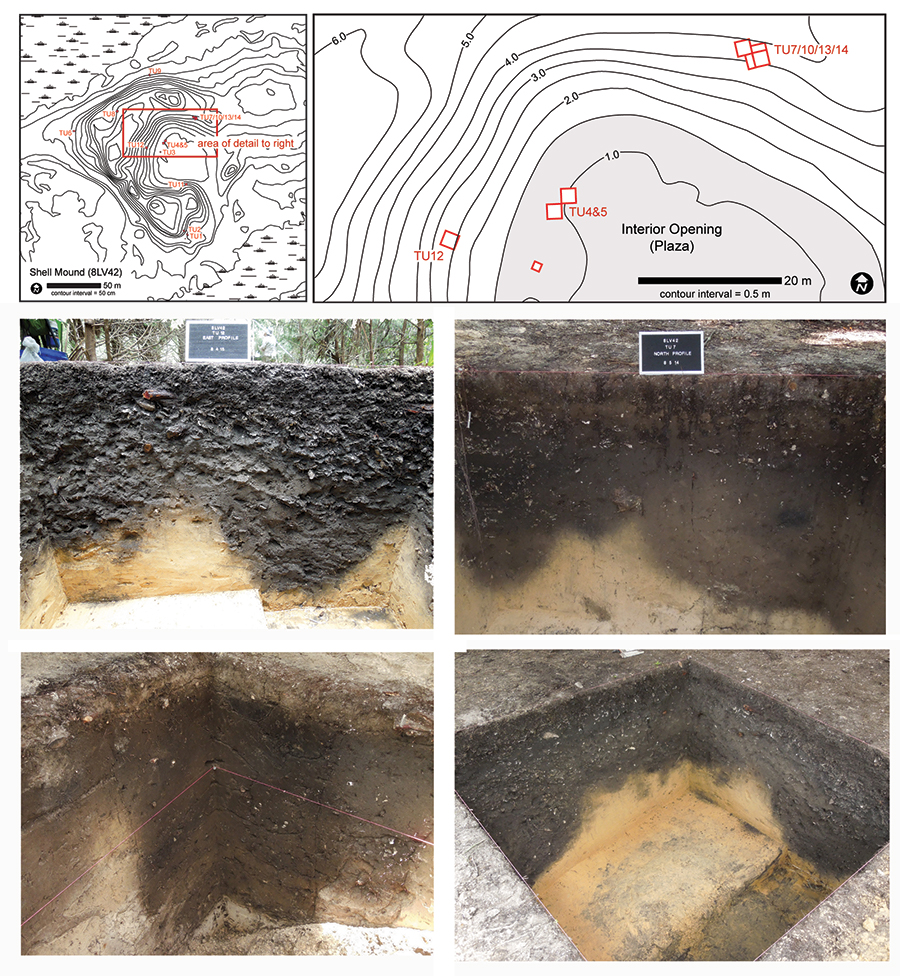

The results of shovel testing on several islands reveal a pattern of intensive occupations. Among them are sites located on the “upland” remnants of parabolic dunes that formed during the last Ice Age, when the study area was 200 km east of the Gulf. Dating to the last 4,000 years, occupation of these sites occurred after global warming brought Gulf waters to the area and converted dunes into a diverse array of islands and peninsulas. We occasionally encounter sites known as “shell rings,” which are accumulations of shell and other matter in rings of various size. Shell rings throughout the coastal Southeast typically date to the Late Archaic period, but those of the study area are less than 2,000 years old. When found in isolation at places like Richards Island, shell rings express low relief, but in at least one case, on Raleigh Island, rings are up to 4 m tall.

The research aspects of the Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey turn on the interests of graduate students and professional colleagues. A diverse agenda of research enhances the value of sites in the refuges to questions of broad historical and ecological relevance. A great deal of work has focused on two civic-ceremonial centers dating to the first millennium CE. Shell Mound and its associated mortuary mounds 12 km north of Cedar Key are the ongoing subjects of research by Ken Sassaman and colleagues. Garden Patch at the north end of the project area, near Horseshoe Beach, is a continuing focus of research by Neill Wallis of the Florida Museum. Underway is the dissertation work of Terry Barbour at the shell rings Raleigh Island; Jessica Jenkins’ study of social movements of the Late Woodland period; and Matt Newton’s survey of the PaleoSuwannee channel.

In addition to these ongoing projects, completed dissertation and thesis research by affiliated members of the LSAS include:

- Mark Donop’s investigations of mortuary activity and associated pottery caches at Palmetto Mound.

- Ginessa Mahar’s study of the technology of fishing, including experiments in mass capture.

- Paulette McFadden’s geoarchaeological investgations of climate and culture change in the Horseshoe Beach area.

- Andrea Palmiotto’s work on effective seasonality of site occupations through analysis of faunal remains.

- Anthony Boucher’s survey of the peninsula connecting Shell Mound with Dennis Creek Mound.

- Joshua Goodwin’s study of avian remains from Shell Mound in support of the inference for summer solstice feasts.

Technical reports of the Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey can be downloaded from the Publications tab of this website. More information on ongoing and archived projects in the study area is available on pages listed under the LSAS menu to the upper left.

Kenneth E. Sassaman

June 2020