Located just north of Shell Mound (8LV42) is an archaeological site that might just be one of a kind. Raleigh Island (8LV293) is a shell-ring complex that had received very little attention until being “rediscovered” in 2010 in response to the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Laboratory of Southeastern Archaeology staff began systematic testing of the island in 2013 as part of our Lower Suwannee Archaeological Survey. Through relatively limited testing we have begun to identify many of the activities that took place on the island between 900 and 1200 CE, the most surprising of which is intensive shell-bead making during a time when marine shell was in high demand across the American Southeast.

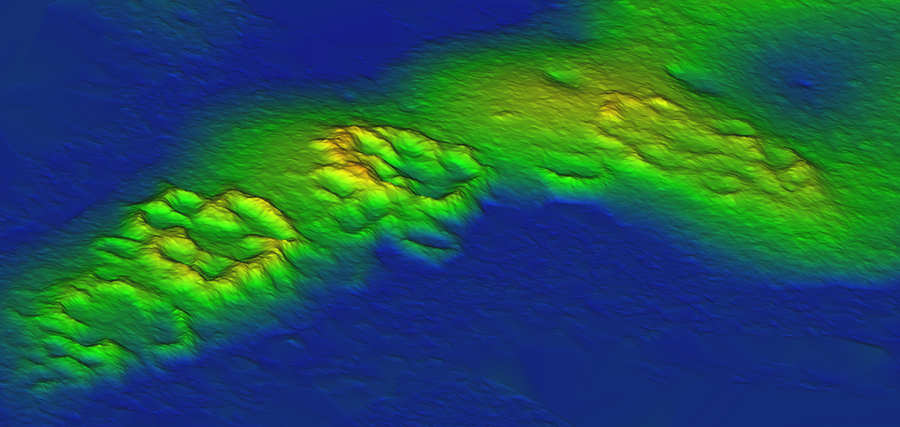

The Raleigh Island site is a complex of no less than 37 shell rings and ridges at the west end of the island. Ranging up to 4 m in height, the rings cluster into four groups of six to 12 rings each. Rings enclose what we refer to as a “living space.” We suspect that each ring was the living space of a household or family surrounding what might be communal space. In addition, a large, rectangular space in one group of rings may have housed a public building or space where group activities occurred. Work is currently underway to better understand the nature of these ring groups and what they can tell us about the people who built and lived in them.

Mapping the surface topography of this complex with conventional surveying instruments was inhibited by dense ground cover. Likewise, the tree canopy of Raleigh Island diminished the resolution of publicly available LiDAR. These problems were immediately resolved by our UF colleagues at GatorEye, who used low-elevation, drone-mounted LiDAR to cut through the canopy. The level of detail provided by drone LiDAR illuminates the topography of all the rings and highlights features not easily seen with the naked eye (Read more on the results of LiDAR mapping in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences).

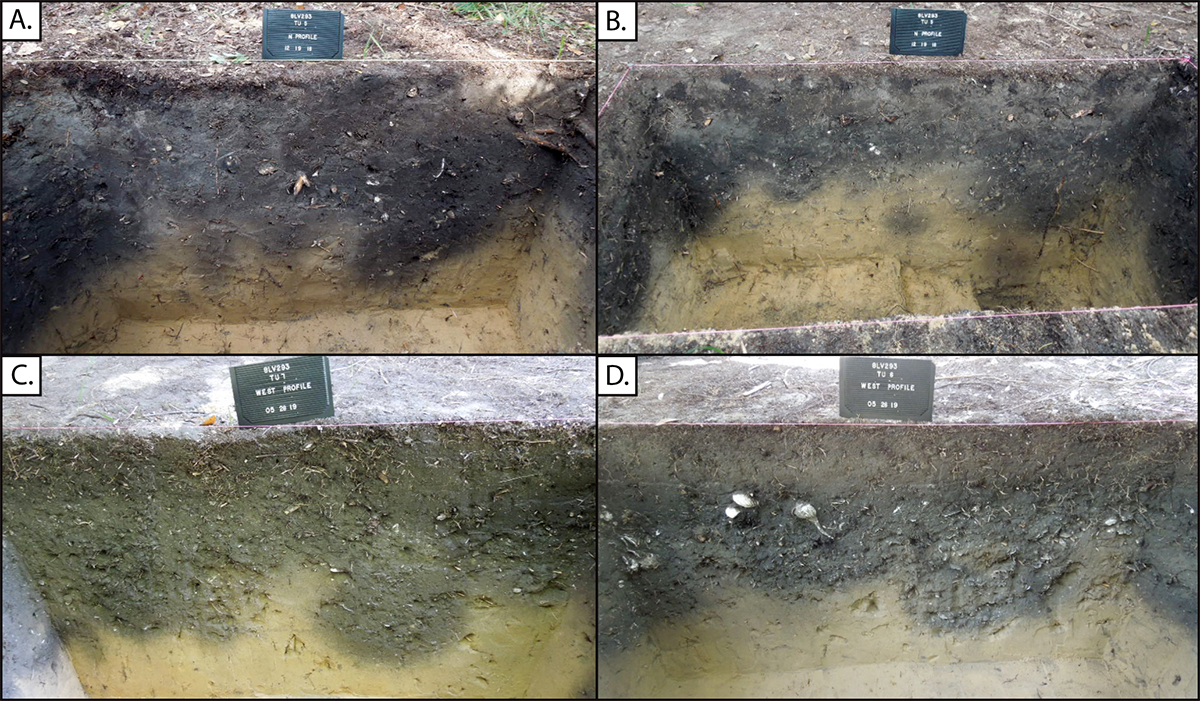

From test excavations we are beginning to understand what went on in the rings. Within each of the rings tested, a dense, organic midden around 60-cm thick hints at the intensity of activities that took place at the site over its 300-year history. Numerous, overlapping pits and post molds varying in size were observed in all test units. In places these features are so dense they are difficult to discern until reaching the base of the midden. Ten radiocarbon dates on charcoal verify that the occupation of rings elapsed over three centuries, between 900 and 1200 CE. Although more dates are needed to substantiate the sequence of occupation, the earliest dates are from rings of groups 1-3. Rings of Group 4 come online around 1000 CE, with Group 2 and 3 rings remaining active, while those of Group 1 were vacated.

The sherds of pottery vessels found at the site are indicative of everyday cooking and serving. Absent are sherds from large, cauldron-like vessels, like those of Shell Mound, which would signal large gatherings of people. Rather, the Raleigh assemble looks to be exclusively domestic. It consists mostly of sherds from plain bowls and pots that were tempered with sand, but also sherds of Hillsborough Shell and Ruskin Dentate Stamped. Several Swift Creek complicated-stamped sherds were recovered from a ring in Group 1, indicative perhaps of the earliest use of the site. Other varieties, such as a simple-stamped ware found in the rectangular enclosure of Group 2, are insufficiently dated to know when they were in vogue over the three centuries of occupation, but they add a measure of diversity that may reflect coeval cultural differences rather than change.

All test units also contained large quantities of chipped stone debris from toolmaking. Most of the formal stone tools recovered are microliths, or very small stone tools, used for activities like drilling, carving, and etching. Microliths were made using a technique called hammer-and-anvil, or bipolar reduction, whereby chert cores are placed on a hard flat surface (anvil) and then impacted with a hammerstone. The technique creates prismatic shards that were then either modified further or used as is, presumably affixed to some sort of handle. Many were undoubtedly used to drill the small holes of shell beads, the by-products of which are abundant throughout the site. In fact, much of the lithic material recovered from the site appears to be related to the manufacture of these small drills.

Beads were crafted from the shells of a marine gastropod called the lightning whelk (Sinistrofulgur sinistrum). With its sinistral spiral, the lightning whelk is known as a spiritually powerful medium throughout Native America. Shells of this species were imported in large quantities to the emerging chiefdoms of the continent, such as Cahokia, IL; Moundville, AL; and Etowah, GA, beginning around 1000 CE. At Raleigh Island, all stages of lightning whelk bead making have been identified, and work is underway to further characterize the shell assemblage at the site. It remains to be determined if any of the beads made at Raleigh Island found their way to places like Cahokia, Moundville, or Etowah. The by-products of shell making at Cahokia attest to the importation of whole shell, but that does not preclude the importation of finished beads too. On-site manufacture of beads at Moundville and Etowah has not been documented, so beads at these more proximate sites must have been imported in finished form.

There is still much we do not know about Raleigh Island, and ongoing analysis aims to fill in some of the gaps. In order to understand what the several rings and ring groups represent socially, artifacts recovered from a sample of rings are being analyzed to document variation in tool making, bead production, pottery manufacture, and food preferences. Did households operate independently? Was bead production segmented across the community? How did gender relations influence production? Beyond questions related to the site itself, Raleigh Island was part of a larger social network coalescing around 1000 CE. Given that only three finished beads have been found thus far, where did all the final products go? Lightning whelk beads are found across the Southeastern US, but little attention is paid to how the communities at the source of shell factored into this extensive trade network. Was the community on Raleigh Island working autonomously or were they under the sway of clients who lived elsewhere?

Raleigh Island is located on protected federal land. Our work there requires a permit from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, which manages the Lower Suwannee National Wildlife Refuge. While Raleigh Island is not open for visitation, we hope that our investigations will enable the public and the profession alike to appreciate the information potential of this unusual site. As with most other coastal sites in Florida, Raleigh Island is subject to shoreline erosion and related impacts of climate change. Before it succumbs to inundation in the decades ahead, we hope to be able to narrate a relatively complete history of its role in both the rise of Mississippi chiefdoms in the American Southeast, as well as its heritage and influence in the local coastal landscape of ancient Native America.

Terry E. Barbour

July 2020